The scope of the problem

Since November 2022, the kinds and scale of threats to traditional forms of assessments and assignments have increased dramatically. There is no one solution, and certainly no “tech fix” that can make it go away. Realistically, unless work is done under supervision in a classroom or online using Lockdown Browser (though it is not a complete solution), or Honorlock (recommended only for completely online tests), it will be up to your students to use or not use AI.

The list of threats is growing. It includes:

- The use of chatbots and apps.

- AI embedded in browsers, including Google Lens built into Chrome and Pilot in Edge.

- AI in search engines.

- The use of AI embedded in other apps (e.g., Google Docs, some versions of Word, Grammarly, etc.).

- AI browser extensions.

- AI agents, including browsers like Comet and Opera Neon built around these agents. Some of these are already capable of doing most of the work in a Canvas course with little or no human intervention.

It is important to remember that AI can be used for almost any kind of media and for virtually any part of an assignment or assessment that is remotely taken or submitted.

AI testing threats and countermeasures

| Threat | In-seat paper | In-seat Canvas | In-seat LockDown Browser | Online Canvas | Online LockDown Browser | Online Honorlock with Browserguard enabled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Plugins | 2. Defeats | Vulnerable | Defeats | Vulnerable | Defeats | Defeats |

| 3. Browser-based tools | Defeats | Makes difficult | Defeats | Vulnerable | Defeats | Defeats |

| 4. Covert use of AI | Makes difficult | Makes difficult | Makes difficult | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Makes difficult |

| 5. Agentic AI | Defeats | Makes difficult | Defeats | Vulnerable | Defeats | Defeats |

| 6. Smartglasses | Makes difficult | Makes difficult | Makes difficult | Vulnerable | Vulnerable | Makes difficult |

- A classic example is the Transcript browser extension that adds buttons to Canvas quiz questions to allow them to be scanned and answered. This may be hard to spot because, while the button position is fixed, its color can be changed to match Canvas.

“Defeats” indicates the countermeasure should completely prevent access to that threat.

“Makes difficult” represents a wide range of difficulty for a proctor to spot the threat in use, but the countermeasure should significantly cut down on use.

“Vulnerable” designates threats that are unlikely to be spotted in a large number of cases.

- Google's Help Me Write, Google Lens/Homework Helper and Gemini in Chrome are all examples we saw in 2025.

- Typical examples are holding a phone in one's lap or, if using Honorlock (HL), holding it outside of the camera's view. In the latter case, it can be used to scan questions on the computer screen and provide answers.

- Perplexity's Comet, OpenAI's Atlas and Opera's Neon are all examples.

- As of February 2026, Meta Ray-ban Display Glasses with a bracelet-style wrist controller are the most frequently mentioned concern, but others are emerging. To be a threat for in-seat or HL tests, a sticker that blends in with the frames must be placed over the telltale light that indicates the camera is on or the indicator LED must be physically disabled in the glasses, voiding the warranty. Other brands are promising their upcoming smartglasses will not have a telltale light. Waveguide technology will make it difficult for proctors to determine if an image is being shown on screen. Note that these can be a student's rather expensive prescription glasses. Expect to see this as more of a problem late 2026 and early 2027.

Managing plagiarism in student work

What is AI plagiarism?

At its simplest, AI plagiarism is creating and using content without attribution. That differs a little from conventional plagiarism, which is simply using someone else's content without any creativity at all. The complexity of the prompt (i.e., the questions and instructions given to an AI) will often determine the quality of the output. It is essential to think in terms of content, not just writing. Most AI is multimodal, i.e., it can handle most forms of input and output. This means that AI can be used to create almost any kind of content for assignments.

With AI, it can go far beyond simple plagiarism. AI can be used in any part of a written or other assignment. Would you consider it plagiarism or cheating if a student uses an AI for any of these? Where would you draw the line?

- Brainstorming

- Research

- Outlining

- Abstracts

- Notes or bibliography

- Rough drafts

- Editing or proofreading

- Making suggestions to overcome writer’s block in specific parts of the content

- Polishing the final product (including the use of AI by non-native speakers to “Americanize” their writing)

Of course, it is not plagiarism or cheating if you specifically allow the use of AI for all or specific tasks. It is essential to communicate what is and is not allowed and why. Overcommunicating, perhaps both in-class and in written instructions, is advised.

What should I look for when reading a paper?

There are also telltale signs to look for, and, as the technology evolves, these may change. The following is based on ChatGPT.

Look at the complexity and repetitiveness of the writing. AI tools are more likely to write less complex sentences and to repeat words and phrases often.

One telltale sign of an AI-generated paper in 2023 was made-up or mangled citations, which might include DOIs for other articles or that pointed nowhere; a mixture of correct and incorrect author, title, and publication information; books and articles that do not exist; and nonsensical information. Due to improvements in the tools and their access to web searches, this is less likely to happen in 2024 and may continue to improve; however, the tools still make mistakes, and the citations produced may not contain information pertinent to the information in the paper. It is still worthwhile looking for egregious factual errors. At least on some subjects, chatbots will insert information that is flatly impossible. While students might do this, in combination with other factors, the errors are often things that are unlikely to be made by a human. Remember, AI tools do not understand what they are writing. The phrase "stochastic parrots" is often used to describe them, as they work out what words are most likely to follow other words and string them together.

Look for grammatical, syntax and spelling errors. These are more likely to be mistakes a human author would make.

If you have a writing sample from the student that you know is authentic, compare the style, usage, etc., to see if they match or vary considerably. If you do not have an existing writing sample and are meeting with the student, ask them to write a few paragraphs in your presence to create one.

Does the paper refer directly to or quote the textbook or instructor? AI is unlikely to have textbook access (yet) or know what is said in class (unless fed that in a prompt).

Does the paper have references that refer back to the AI tool by name or kind? In some cases, students have left references to ChatGPT made to itself in the text.

Consider giving ChatGPT your writing prompt and evaluate the output compared to student submissions.

What are some ways I can structure writing assignments to discourage bad or prohibited uses of AI?

- Consider requiring students to quote from specific works, such as the textbook or class notes. AI is unlikely to have access to either, though students might include quotes in the writing prompt.

- Add reflective features to the assignment; these could be written or unwritten, such as having students discuss live, or record (e.g., VoiceThread, Panopto), what they have found in their research and reflect on their writing.

- Use ChatGPT or other tools as part of the writing process – for instance, brainstorming – but also have students critique the work, consider the ethics of using AI, etc.

- Creating a writing assignment with scaffolding (including outlines, rough drafts, annotated bibliographies, incorporating feedback from peer reviews and the instructor, etc.) could help with some aspects of AI use. It might not be very effective on the outline or first draft, as those may still be generated by AI. Asking for an annotated bibliography would, with the current limitations of the software, be something it could not do with much success.

- Contact your campus teaching center, writing program or instructional design team for ideas and help working out assignments that promote the use of AI in positive ways or mitigate possible harms.

Presentations and infographics

The problem

As with writing, you need to decide how much, if any, AI use is acceptable. There are at least five tiers of use to consider with presentations:

- Limited use for things like brainstorming and polishing.

- Using generative AI to create clip art, bullet points and other artifacts to include in individual slides or infographics.

- Using AI to create entire slides or infographics.

- Using AI to generate whole presentations.

- Use of avatars and text-to-speech tools to create prerecorded presentations.

Tools for this range from AI chatbots, like ChatGPT, Gemini and Copilot, to stand-alone presentation generators, like Gamma, and text-to-speech software ElevenLabs. AI is integrated into Google Slides and MS PowerPoint, and AI can be integrated into web browsers using extensions.

You may encounter students who are well-versed in using AI in presentations and who have been taught that its use is generally acceptable. Some instructors feel that using AI tools to help create presentations and related media, such as infographics, is a vital skill in the current work environment, so they teach or coach students to use them well. This includes crafting good prompts, reviewing and revising the material to ensure they understand it before they give the presentation and rehearsing to polish the performance. As with other kinds of assignments, be specific in the syllabus and/or assignment instructions about what you do and do not allow, as well as why, so that students understand the value of the assignment and the policy.

Some Telltales

Images are a good place to look for clues. Most tools are still incapable of creating accurate, detailed infographics or diagrams. In fact, many still have difficulty inserting text into an image, exhibit limitations with spatial relations or basic physics and still generate images with cartoonish or hyperrealistic looks. However, the days of odd numbers of fingers and other telltale signs we relied on over the past three years are largely gone. When shown on a large display, many problems may be more visible.

Numbers and statistics are other items to evaluate. Can the student provide real sources? In many cases, AI makes up numbers. When asked about falsified data, chatbots may give replies similar to this one from Gemini: "The data presented in the charts within the infographic is illustrative and was invented to support the narrative of the presentation. It is not derived from specific real-world studies or datasets."

Short bits of text in a presentation or infographic may not lend themselves to the usual screening tactics for AI use; however, the speaker's notes may provide instructors with sufficient text to notice unusual usage patterns.

If the student(s) giving the presentation do not appear to understand it or do not engage with the material easily, that can be a strong clue that something is amiss.

Some guides suggest checking PowerPoint Properties or Version History. The former is easily modified and falsified. The latter does not appear in files downloaded from Canvas. It could be useful if the file is housed online in tools like Google Slides.

Example

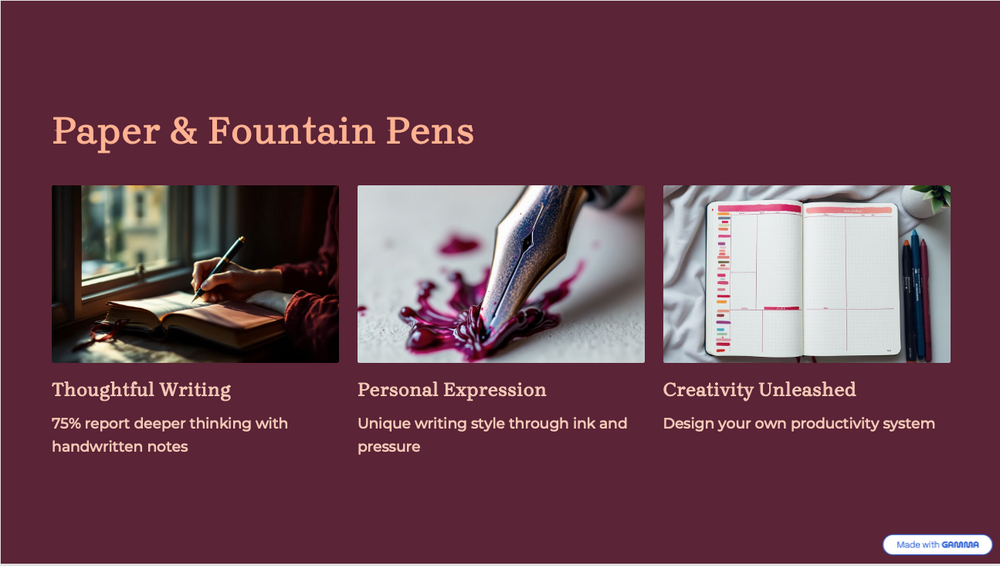

Figure 1: Example of a slide generated with Gamma AI.

Consider this slide (Figure 1, above).

- The three images are all AI-generated.

- The one on the left, a close-up of writing in a notebook, is superficially good, but the position of the writing hand is unnatural. Viewed up close, it is not clear if there is a left hand at all.

- The center image should show a close-up of a fountain pen nib writing on paper. The nib is not a fountain pen nib and, more obviously, it is leaking ink.

- Meanwhile, the image on the right, apparently of a planner notebook, depicts nonsense words and random blocks of color along the left margin.

- The figure of 75% in the phrase "75% report deeper thinking with handwritten notes" is a complete fabrication. The phrase "deeper thinking" lacks clarity but sounds good.

- In this example, the slide is watermarked, but this is trivial to remove by editing the slide master.

Infographics contain similar problems to the presentation in the previous example. Some additional things to look for are:

- If the infographic is presented as HTML, and you are comfortable with HTML code, look at the code, but note, you may be unable to easily differentiate between AI and a human using traditional coding tools.

- If it is presented as a PDF, look for odd line breaks that might reveal that it was printed or saved from an AI on the web.

- Metadata also sometimes reveals the source of a PDF.

Addressing cheating with AI

Threats

There are a variety of current and potential threats from AI, especially online versions.

Established threats include:

- Consulting chatbots for help with test questions, either on the same computer or on a different device.

- Browser extensions that can scan and answer objective questions in Canvas quizzes or provide translations.

- AI features built into browsers or operating systems that write or help write text and can be used to answer essay questions. These include Google Lens and Help Me Write.

- Apps that can photograph/scan math problems and provide answers and complete solutions.

- Multimodal AI apps that can photograph/scan questions and provide answers or identify images.

- AI search built into browsers that provides answers much quicker than conventional search.

Emerging threats include:

- Agentic browsers that may be able to take a test without human intervention. As of 2025, these are only beginning to appear, and their actual capabilities remain unclear.

- Smart glasses, such as Ray-Ban Meta glasses, but their use in cheating appears to remain more theoretical in mid-2025 than real. Since these can be prescription glasses, it may not be possible to ban them altogether. A number of other AI wearables are being developed, some by major corporations, but their usefulness for cheating is unclear.

As AI continues to be added to almost all types of applications, operating systems and hardware, it may be better to stop thinking of AI as tools and more in terms of an all-pervasive part of the environment, or as an environment itself.

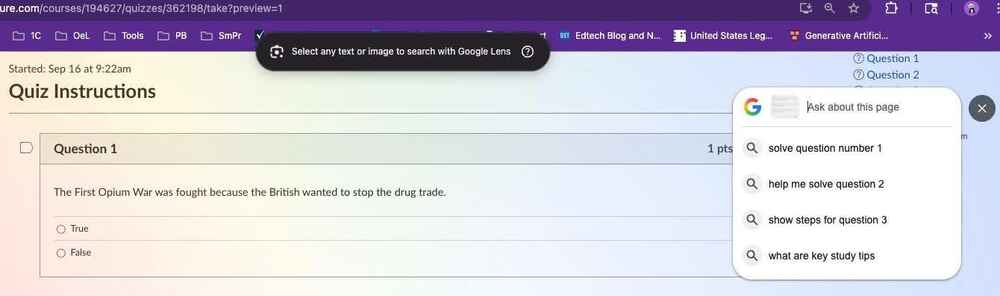

Two developments are especially troubling. One is the rise of AI tools in browsers. The other is the rise of AI agents, including agentic browsers. For instance, in an unproctored test, a student using Google Chrome could use Google Lens (figure 2) or Help Me Write to answer any objective or written questions on a Canvas quiz or test.

Figure 2: Google Lens opened from within Chrome.

Agentic AI is a larger threat, one whose capabilities are just becoming evident. For a short demonstration of the ChatGPT Agent checking Canvas for assignments, then completing a brief writing assignment for the user, see David Wiley’s video, Using ChatGPT's Agent Mode to Autonomously Complete Online Homework. Other experiments have demonstrated the ability of similar tools to take tests autonomously.

Proctoring platforms

Respondus Lockdown Browser

Lockdown Browser is a custom browser that locks down the testing environment within Canvas. When students are required to use Lockdown Browser for a Canvas quiz, they are unable to print, copy, go to another URL or access other applications. Lockdown Browser does not record the student’s screen or environment.

Honorlock

Honorlock allows the instructor to enable options for automated verification and monitoring of the test taker, their environment and their computer screen. Features include content protection, blocking other extensions such as ChatGPT, a panorama of the room, recording of ambient noise and analysis of the student’s on-screen activities and eye and facial movements. Honorlock offers recording of the user’s webcam and monitor feeds so you may review their environment and the test screen during an exam.

Browser tools

Mainstream browsers increasingly have AI features. Examples include Google Chrome's Help Me Write and Google Lens, both generally available to users, and its new Gemini in Chrome, currently available only for Pro users. The former is available from a right-click menu in almost any text box, including Canvas Essay Questions, to write and polish short text. The latter is a more general chatbot interface available at any time through a browser button and able to read the current page. Fortunately, at this time, they appear in such a way that a proctor, human or automated, should have a relatively easy time catching them, as they appear on screen in obvious ways.

Browsers built around AI agents are beginning to appear in limited numbers. For the moment, we do not know the extent of capabilities against online quizzes and tests.

Browser extensions

Browser extensions for test cheating have become more important recently. The best known of these is probably Transcript. It works by adding a button (which can be customized to make it difficult for a face-to-face proctor to see) into Canvas questions. It works by scanning objective questions and answering them using AI.

Two ways of defeating extensions are to use Lockdown Browser, which does not accept extensions, or use Honorlock with its BrowserGuard feature enabled. This blocks any extensions on the application's large and growing list of malicious browser extensions.

Some extensions may have similar capabilities to Chrome's Help Me Write tool mentioned above.

Third-party tools

Little is known about the vulnerability of third-party courseware that has its own testing software. Most of the same attack vectors that can compromise Canvas quizzes are available to students taking tests with McGraw Hill, Cengage, Pearson or other tools from publishers.

Some of these companies have deals with Respondus or one of the other online proctoring providers, in some cases with both no-extra-cost and student-paid versions. Under the Simplified Tuition Rules, you may not use the student-paid version and should check with your campus before using the no-cost version. These typically lack important features. We recommend using Honorlock with courseware for online test proctoring.

Unproctored Canvas quizzes

Many instructors are used to improving exam security with the practices listed below. For AI, only items eight and nine have any effect at all. Of those, number eight would be slightly effective with some types of AI cheating techniques. Number nine is more effective but only feasible with small numbers of students.

- Shuffle answers.

- Shuffle questions.

- Show only one question at a time, and do not allow backtracking.

- Add multiple questions on the same topic to question banks so students get different questions, not just the same questions in a different order.

- Add and remove some questions from question banks each semester.

- Do not reuse tests without making changes from one semester to another.

- Avoid publisher question banks and tests. Those may be more likely to be available from cheating sites online.

- Keep testing times and windows short.

- Add a follow-up assignment in which students are required to pick one question and explain in detail how and why they answered it in the way they did.

AI detectors

What is an AI detector?

These are applications that predict the likelihood that writing was created by an AI or a human. Typically, these look at characteristics of the writing, particularly how random it is. Humans tend to use a greater variety of words; have more randomness in their spelling, grammar and syntax; and generally have more complexity than an AI. Some will give a verbal or visual indication of how strongly it finds the text to be from a human or an AI. Others return results in terms of perplexity (a measure of randomness within a sentence) and burstiness (a measure of randomness between sentences) with scores, graphs or color coding. Lower perplexity and burstiness scores are more likely to be from an AI, with higher ones pointing toward human authorship.

Why does UM not license or recommend an AI detector?

We highly discourage the use of ChatGPT or similar AIs (e.g., Bing AI Chat, Bard, Claude) to determine if a paper was written by an AI or a human. They produce false results at a very high rate, regardless of who or what wrote the paper. They will also produce plausible rationalizations to defend their answers if asked. This is the worst way to determine AI plagiarism.

There are also AI detectors for other types of content. These should be regarded with the same caution and reservations.

Are AI detectors reliable?

No, at best, they are indicative. Published claims of reliability vary greatly. Some detectors claim false positive rates under 1% (i.e., 1% of those submissions flagged as containing AI-content will actually have no AI-generated content). To put that into perspective, had we run Turnitin's AI Indicator on all of the papers submitted to Turnitin across the UM System in 2024, we would have had a minimum of a few hundred false positives. For some detectors, false positive rates may still be many times higher for non-native writers of English. This is also potentially true for students who attempt to write in "academic style" and for certain types of neurodivergence. In all three cases, the use of a smaller or controlled vocabulary and stilted writing style is difficult to distinguish from AI.

Less discussed, but also important, is the false negative rate. These are papers with significant AI content that are missed by detectors. Despite claims for specific detectors against specific AI models, there is evidence that they may miss as much as 15% of AI content. Given the existence of tools specifically designed to defeat AI detectors and fairly simple expedients involving light rewriting of AI content, these rates could be much higher.

While detectors continue to improve, this should be viewed as an arms race rather than a stable situation. For instance, recent advances with ChatGPT (particularly using GPT-4) show that it is possible to coach it to write with more complexity and fluency, making it harder to detect. This is particularly true of students using well-engineered prompts. By prompt engineering, we mean the creation of fully developed questions and instructions (sometimes including data) to elicit the desired kind of results from the AI.

For these reasons, as well as the privacy and other issues discussed below, the use of AI Detectors is strongly discouraged.

A note about Turnitin

You may have heard that Turnitin released a preview of its AI-detection tool in April 2023. Due to concerns about some of its features, all four campuses have decided not to implement this feature.

Please be aware that the regular version of Turnitin available across the UM System cannot detect content from ChatGPT or other AI tools. Even running a prompt for your writing assignment through an AI tool (e.g., Gemini, ChatGPT, or Claude) several times, then uploading those to Turnitin, is unlikely to match submissions that include AI. In most cases, the AI will produce results with sufficient variation to fool Turnitin.

Privacy and other concerns

The University has not vetted free AI detectors. This is strictly a case of use at your own risk for now. You should never feed them any content allowing identification of the student. We also do not know the specifics of whether or how they store or use content. The same applies to feeding text from student papers back into an AI for evaluation.

Many faculty will enter parts of student papers into Google or other search engines to try to find matches, so this may not seem so different to you. You may wish to consider the differences between that and pasting or uploading all (or large parts of) a paper into an application. Beyond privacy, there may be questions of student copyright to consider.

Because we have a license and agreements with Turnitin that cover FERPA and meet the University's interpretation of student copyright, these considerations do not apply to Turnitin tools.

Resources

- AI Plagiarism & Cheating: Papers, a video presentation of part of the material presented above.

- AI Plagiarism & Cheating: Tests, a video presentation of part of the material presented above.

- Aviva Legatt, Colleges and Schools Must Block and Ban Agentic AI Browsers Now. Here’s Why. Forbes, September 25, 2025.

- J. Scott Christianson, End the AI detection arms race: Scott Christianson (MU Trulaske College of Business), discusses reasons to move away from high levels of concerns about AI plagiarism in the "End the AI detection arms race" journal article. He suggests moving toward engaging with technology to benefit both students and professors.

- David Wiley, a short LinkedIn post on using ChatGPT’s Agent Mode with Canvas. This is the source of a video linked in this article but included additional discussion.

- Sarah Eaton, 6 Tenets of Postplagiarism: Writing in the Age of Artificial Intelligence: Sarah Eaton (University of Calgary) is a scholar studying academic integrity. She argues that our ideas about plagiarism are outdated and need to evolve along with the technology.

- Turnitin AI Writing Resources (Turnitin LLC, 2023): Turnitin has created several documents (including rubrics) for working with the challenges of AI writing.

- James Zou, et al., GPT Detectors Are Biased Against Non-Native English Writers is a study of how AI detectors give high percentages of false positives to papers written by non-native English writers. It also shows that the papers are likely to fare better if polished by an AI.

- Lori Salem, et al., Evaluating the Effectiveness of Turnitin’s AI Writing Indicator Model looks at the Turnitin AI Indicator in depth, noting especially its difficulties with hybrid texts and that there seems to be little relationship between the flagged text and those passages actually written by AI.

- UNESCO guide to ChatGPT and Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education contains a primer on AI, suggestions for working with students, considerations of different types of assignments, as well as ethical and institutional considerations.

- ChatGPT, Artificial Intelligence, and Academic Integrity, MU Office of Academic Integrity statement on GenAI and plagiarism/cheating.